How To Hold People Accountable Without Shame

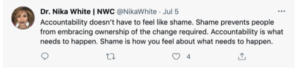

We know holding folks accountable for saying or doing harmful things is important to DEI. Without the checks and balances system, where would we be? But I’ve noticed a trend in how we approach folks we’re calling in: people are using shame as a tool to get folks to admit wrongdoing. Shame isn’t the best way to hold someone accountable or get them to change their behaviors. I recently wrote a tweet about this very topic:

Here’s what we all need to understand: Holding someone accountable doesn’t require shame. Actually, there are real and tangible ways you can have an honest and effective conversation with someone without them retreating into shame, anger, and defensiveness.

Here’s how you can hold people accountable without using shame. And if you’re the one being called in, here’s how you can take constructive feedback with openness instead of defensiveness.

Understand that people may not know they’ve caused harm to others

The truth is many people say and do harmful things, and they may not know they’ve done something wrong.

It’s important to understand that harm is inevitable because people are often operating unconsciously. In other words, folks are on autopilot when it comes to their speech and behavior and what comes out of their mouths may not seem harmful to them. But as it turns out, what they did or said was very harmful and someone else has to check them on it.

The key to beginning the process of holding someone accountable is to move with empathy. Both people should understand that making mistakes is a part of being human. And both parties should also move mindfully through these conversations. Here’s how you do that.

If you’re being called in or held accountable, know that you’re not the victim.

Once someone has been called in and both parties are aware of the problem, the mindset should be: “What will my response be now that I’m aware?

Getting called in can make some people defensive, fearful, or feel that others are gaslighting them. In essence, we, as people being called in, become the victims. But we have to realize, no we’re not the victims. The person who is holding us accountable is sharing this issue with us because there needs to be a change in order to reach equity, inclusion, and compassion. There’s no shame in admitting that we’ve brought harm to someone else and that it wasn’t right. But, it’s important to adapt to the feedback we’re receiving and integrate it.

If you’ve been called out, the questions you should ask yourself are:

- What harm was caused?

- What does that mean?

- What was the impact?

- What are the needs of the person who was harmed?

Having empathy for yourself and understanding that biases occur within all of us is another key step. We can’t avoid it. Acknowledging that harm has been done is crucial. When an issue is brought to our attention, what we need to do is think about how that harm has created negative consequences for the other person, the person who’s really the victim. So, we should ask ourselves: what do the people we harmed need at this moment?

Don’t fall into the trap of feeling rushed to be forgiven by the person who called you out. Sometimes your actions or words were so harmful that people aren’t ready to forgive yet. So, give people their space and respect the time it takes to circle back and begin the process of forgiveness.

If you’re the one being held accountable, it’s important you take responsibility and make sure no future harm is created. Apologize, feel atonement, and acknowledge the harm, but commit to not continuing the cycle.

And most importantly, don’t do this work alone. Seek reassurance and support from people who are there for you. Connect with your community and talk out what happened. Ask if they’ve been through the same thing or how they’ve handled it. Seek to understand, reflect, and course-correct. But don’t shame yourself for what you didn’t know. Now, you know, so you can make better choices in the future and that’s what really matters.

If you’re holding someone accountable, your job is not to shame them. It’s to inspire behavior change.

It’s not easy to call someone in with respect and kindness, but it’s necessary in this work. Many people feel ashamed at the moment and can react poorly to being called out. But it’s important for you to practice empathy and self-control in moments like this because the ultimate goal is to encourage a change in behavior. However, shaming the person or reciprocating vengeful words and actions in the interaction is not the way to do it.

First, if you want to hold someone accountable and to be effective, it’s best to focus on the behavior or action, NOT the person. This is important because a lot of people react to being called in as a defect in their character or personality. But it’s not. They’re not the problem. The problem was their words or actions, which can be changed. When you’re calling someone in, focus on what was said or done and how those actions created the issue. Create a separation between the person’s actions and their inherent value as a human.

The reality is some people aren’t culturally competent and may not have the language to respectfully move in certain spaces. It’s a fact that hurt people hurt people. Underneath oppressive remarks, slurs, and comments is, oftentimes, someone acting from a place of hurt. Having empathy for a person that’s hurting doesn’t make what they said or did right, but it does show us a path forward to responding, and it opens us up to being more thoughtful about our approach to behavioral change.

When holding someone accountable, it’s also important to understand the difference between responding and reacting. Reacting means having no thought of the long-term consequences of an action. Responding means being more mindful about effective strategies to increase the likelihood of behavior change.

In the case of calling someone in and holding them accountable, we want to respond, not react. We want to make it clear what was said or done was harmful and here’s why. Reacting with anger, shame, or resentment will likely increase the temperature in the room and encourage defensiveness in the receiving party. Which is helpful for no one and won’t improve the situation.

Helpful phrases to use when holding someone accountable:

So, if you’re ready to have the hard conversation with someone in a respectful and effective way, here are a few phrases you can use to open up the conversation:

- “Tell me more about the way you’re thinking.”

- “Help me to understand your perspective.”

- “What caused you to feel that way?”

- “What do you mean by that?”

- “That’s not a part of our culture.”

- “That’s not okay with me and I respect you enough to let you know.”

- “Have you considered the harm your words and behaviors can have on others?”

- “I’m telling you this because I believe on the issue of bias, we can all learn. It takes a brave spirit for someone to bring forth that constructive feedback.”

Final Thoughts

This isn’t the first and probably won’t be the last time you’ll have an intentional conversation about hurtful words or behaviors. But this can be the first time that the conversation is effective. Again, the goal is to change behavior and to influence another person to reflect on their words and actions in order to course-correct. The more we can remove the barriers of shame and fear, and step into the arena of conversation, enlightenment, and mutual respect, the better our odds are of creating more equity, inclusion, and connection in our relationships with others.